When more and more literary authors adopt science fiction tropes, are we heading to a point where genre will, stripped of its commercial importance, cease to be a useful classification?

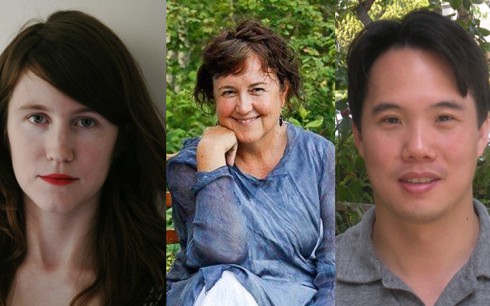

The Center for Fiction kicked off its month-long Big Read on Monday evening with a discussion of utopia and dystopia with authors Anna North (America/Pacifica), Kathleen Ann Goonan (This Shared Dream), and Charles Yu (How To Live Safely in a Science Fictional Universe). Moderated by DongWon Song, an editor at Orbit Books, the discussion quickly turned to the science fiction genre as it applies itself increasingly to books that would be considered literary, or mainstream.

The discussion benefited greatly from the dual perspectives of North and Yu, who are just beginning their careers from outside SFF, and Kathleen Ann Goonan, who brought a wealth of experience within SFF to the table. By the end, one had to wonder whether literary books might, in years to come, be considered a gateway to SFF.

Song began the discussion by asking the authors whether genre is a useful classification for them personally. North and Yu were less inclined to agree that labeling something science fiction, literary, or mainstream was a particularly helpful way to classify a story, as the stigmas that each genre carry in the minds of readers still represent too much of a boundary. A reader should be presented with something they might want to read regardless of what it’s been classified as. (North in particular was very happy to discover her book being recommended alongside China Mieville’s The City and The City on Amazon.) Yu also specified that he would favor recommendations that cross genres.

Goonan herself finds a lot of use for genre as a classifier, noting that strong science fiction tends not to be subtle about being science fiction, and that it would be a bit too homogenizing to dismiss the natural boundary between SF stories that utilize science fiction elements far more intensively than literary stories. There is a flavor to science fiction, Goonan said, that can’t be found in mainstream, and that flavor offers a specific challenge to any writer who wants to work with it. Science fiction can provide new universes, beautifully written and of incredible depth. (Here, North agreed, lamenting that the stigma that SF can’t have beautifully written prose is still very much present.)

The conversation moved further into examining genre elements in mainstream fiction as Song asked whether a science fiction idea can serve to expel a reader from a mainstream fiction story. And in the same vein, was it important for mainstream authors such as North and Yu to utilize science fiction tropes and markers?

Charles Yu found such markers fundamental to the atmosphere of the world in his novel, How To Live Safely in a Science Fictional Universe, as the main character exists in a small alternate timeline. He utilized tropes more to furnish the context of the story than to inform or drive it, lifting other pop culture in much the same manner.

Anna North wasn’t as aggressive in regards to the setting of her book, America/Pacifica, but noted that younger writers live, work, and consume in a world that has a larger acceptance of geekdom and its tropes, which invariably informs how one structures one’s own story and the circumstances they’re interested in talking about.

Kathleen Ann Goonan agreed with the assertion that geekdom is enjoying greater appeal and added that this is also in part to older writers and readers being able to experience, to some extent, the worlds and futures predicted in their favorite science fiction stories. Younger writers and readers place stories within contexts they’re familiar with, and increasingly that context is informed by science fiction becoming science fact.

A reader used to mainstream literature, Goonan added, ultimately won’t be thrown out of a story by a large science fiction concept as long as that concept is conveyed through character. Time travel, the authors spoke, is a great indicator of this. Yu’s own book deals with using time travel as an emotional device to make his main character experience (or re-experience) regret. One of the seeds of North’s book was the appeal of looking at our current time through the lens of nostalgia, and mainstream books like The Time Traveler’s Wife make heavy use of science fiction ideas to tell a character story.

Which is not to say that a big SF idea can be dashed off in favor of a character story, which became apparent as Song took the discussion into the practice of worldbuilding. Goonan, a famed worldbuilder herself, pointed out that worldbuilding and hard science backed up by research is important to the background of a story and helps to keep the reader focused on the story itself by not allowing them the space to stop and question an author’s viewpoint.

Both North and Yu discovered the same thing while writing their novels, and at one point what Yu thought of as a confining process was actually liberating in that it gave his characters directions to go in that were more firm. In that sense, worldbuilding became the only way to move forward, even though the science fiction tropes in his book were mostly limited to atmosphere. Worldbuilding, Goonan pointed out earlier on, is hard to stop once you start.

And although this was not explicitly stated during the discussion, that may just be where these authors find themselves heading. Once you’ve melded mainstream or literary character stories with science fiction elements, once you’ve created a world to struggle within, it’s hard not to keep exploring. Genre might indeed become a useless classification because everything might, at some point, be genre. At least for Yu and North. And if mainstream that utilizes science fiction can provide a gateway to harder SF for the writer, perhaps it will for the reader?

This wasn’t all that was covered in the discussion that evening. (It was a dystopia panel, after all.) Keep an eye on the Center for Fiction’s YouTube channel for video of the full discussion, and take a look at their calendar this month for more exciting talks.

Chris Lough is the production manager for Tor.com.